Naomi Mishima

第12回建友会年次総会を開催

11月20日建友会2025年度の年次総会が、ガーデナーズ協会2階会議室をお借りして開催されました。

26名の会員が会場に来場して出席し、2名の会員がZoomにて出席しました。

年次総会の開始に先立ち、松原会長より挨拶、穴澤役員、和田会計役員から2024年の活動、会計報告がなされました。その後、2025年度の役員として、松原昌輝が会長、Thomas Plamerが副会長、和田健治が会計、三河、伊藤、吉武、花木、穴澤、牧田、村山が役員の総勢10名が立候補・再任されました。

引き続き2025年度の活動、会計計画案が説明され無事年次総会は終了しました。

年次総会終了後、食事と歓談をしたのち、8名の2024年度新規会員の方より、自己紹介・プレゼンを行ってもらい会員間の交流を深めました。

会の最後は、トム副会長の閉会の挨拶により締めくくり、2025年度も、役員・会員力を合わせ、建友会および日系コミュニティをより一層盛り上げていくこと決心しました。

(寄稿 建友会)

合わせて読みたい関連記事

日本カナダ商工会議所クリスマス・パーティと第4回小松和子アワード授賞式

🎵ジングルベル🎵サンタが町にやって来る🎵

2024年12 月17日、世界各地からの人々を魅了するバンクーバー・ガスタウンは、高層ビルの脇にありながらも、人々の歴史を感じさせる。

見事な壁画や、アンティーク家具を備えたイタリアン・レストランを会場に開催されたのは、日本カナダ商工会議所主催のクリスマス・パーティ。

さまざまなバックグラウンドを持つ、バラエティに富む参加者たちの笑顔に包まれ、煉瓦造りの暖かみの中で、世界がひとつになり、新しい歴史を築き始めるパッションに溢れた。

総勢36名が集った中、ゲストの髙橋良明バンクーバー総領事は、アフガニスタン赴任時のエピソードを、ユーモアたっぷりに語り、大きな喝采を得た。

例年、クリスマス・パーティにおいて、日本カナダ商工会議所の『小松和子アワード』の授賞式が行われ、本年度は6名の受賞者が選ばれた。

3つのカテゴリーを持つ同アワードは、日本とカナダをつなぐ活動を通して、日系カナダコミュニティに貢献した人々に贈られる。

カテゴリー 1:

ジョージ・シム氏(ライオンズ・ノースショア・ユース・エクスチェンジ会長)長年に渡り、ノースバンクーバー市と千葉市の姉妹都市交流を推進して来た中心人物。

村上陽子(グラッドストーン日本語学園 学園長)50年に渡り、卒業生延べ2千人以上の日本人やカナダ人に日本語を教えてきた。

カテゴリー2:

ケーシー若林氏(日本カナダ商工会議所副会長)10年間に渡り、日本カナダ商工会議所の事務局長、副会長を歴任。

鈴木美和氏(日本カナダ商工会議所理事)理事に就任して 2年目で、積極的に会の活動を行い、特に本年は UBC キャリア・ネットワークの学生たちと日系コネクト・フェアやグローバル社会で活躍できる若者養成のための「繋ぐ塾」を開催。

カテゴリー3:

清野健二氏(バンクーバー神輿櫻會)長年お神輿を担ぎ、8年前から神輿グループ、櫻會を創設。

ダグ・マスハラ氏(テツ太鼓)日本の伝統和太鼓をカナダの子供たちに教えて22年。

最後に、サミー高橋会長は、日本カナダ商工会議所の存在意義と役割について「この会は日本人以外の人たちもメンバーとして含み、理事会や年次総会、クリスマス・パーティなどは、すべて英語を公用語として使用している。日本とカナダをつなぐマルティカルチュラルな人々を結ぶ連邦政府が承認した唯一の日系ビジネス団体として、ビジネスのみならず、文化、教育、観光等の分野で活動しいることが特徴である」と語った。

撮影 編集 吉川英治

(寄稿 日本カナダ商工会議所)

合わせて読みたい関連記事

23 ☆ワイングラス「数え方」の奥深さ !

日本語教師 矢野修三

師走も半ば過ぎ、「今年も残り少なく・・・」こんな挨拶言葉がふさわしい時期になり、あちらこちらで色鮮やかなクリスマスのイルミネーションが目を楽しませてくれる。忘年会など飲み会も重なり、何かと忙しい年の瀬である。

飲み会といえば、カナダに移住してから、ワインを飲む機会が増え、だんだん好きになり、飲み会での、いかにも日本的なスタートの決まり文句、「最初はビールで・・・」が、今では「最初からワインで・・・」に変わってしまった。

そんなワイン好きな上級者と忘年会を行なった。居酒屋風パブで4人、輪になってワインを飲む「輪飲(ワイン)会」のスタート。早速「赤だ、白だ」と、いろいろワイン談義が始まり、特にS君はワイングラスの持ち方などにも結構うるさい。

そこで、この機会にワイングラスの「数え方」を話題にした。先ず、日本語ではどんな数え方をすると思うか、聞いてみた。すると「1個、2個」ですね。でも「1つ、2つ」かも、また「1本、2本」も・・・などいろいろな意見が出たが、何か特別な「数え方」がありそうですね。さすが、なかなか察しがよろしい。

早速、ワイングラスを片手に、勉強会を始めた。先ず、「1本、2本」は、うーん、気持ちはよく分るが、残念ながらワイングラスには使わない。でも「1個、2個」や「1つ、2つ」はどちらも使われており、全く問題ない。

しかしながら、正式な数え方は・・・、ワイングラスの細長くなっていて、手で持つ部分、英語ではステム(stem)だが、日本語では「脚」。この漢字の音読みは「キャク」、訓読みは「あし」であり、格式高い店などでは、「1脚(きゃく)、2脚(きゃく)」と数えるよ、と説明した。

すると、なるほど、と感心しきり。加えて、お客さまに出すグラスの場合は「おもてなし精神」を発揮して「お客」の「客」を使い、「1客、2客」と数える場合もあると補足したら、びっくり。

さらに、ワインが入っているグラスは中身、つまり「飲み物」に焦点を当てて、「1杯、2杯」と数える場合もあり、と告げると、英語では考えられず、ちんぷんかんぷん。確かに、こんなこと生徒に教える必要はないが・・・、状況に応じて使い分ける日本語ならではの細かな表現方法。

そこで、おまけにこんな話もつけ加えた。日本ではそろそろ年賀状を準備する時期。でも最近はSNSなどの影響もあり、年賀状離れがかなり進んでいるようでさびしい限りだが、この年賀状の「数え方」である。

間違いなく、買うときは「1枚、2枚」と数えるが、お正月に友達から届いた年賀状は、日本人はさり気なく、「1通、2通」と数えたくなる。それはお互いの心が通じたから「通」を使うんですよ、と講釈を垂れると、すごい、すごいの連発。教師として、ほんわか気分に。

こんな話をしていたら、ワインもかなり進んだ。そしてS君曰く、茶目っ気たっぷりに「脚の長いワイングラスを二脚買って、脚の長い彼女とボジョレーヌーボーが飲みたいです」、さらに「日本語って本当に奥が深いですね。ワインと同じように」と、締めの挨拶。奥が深い忘年会であった。

「ことばの交差点」

日本語を楽しく深掘りする矢野修三さんのコラム。日常の何気ない言葉遣いをカナダから考察。日本語を学ぶ外国人の視点に日本語教師として感心しながら日本語を共に学びます。第1回からのコラムはこちら。

矢野修三(やの・しゅうぞう)

1994年 バンクーバーに家族で移住(50歳)

YANO Academy(日本語学校)開校

2020年 教室を閉じる(26年間)

現在はオンライン講座を開講中(日本からも可)

・日本語教師養成講座(卒業生2900名)

・外から見る日本語講座(目からうろこの日本語)

メール:yano@yanoacademy.ca

ホームページ:https://yanoacademy.ca

「年の瀬*廻りつづける街と人」

カナダde着物

第66話

*四季折々の着物と歩んだ一年*

今年も残すところわずかとなり、年末のご挨拶を申し上げる時期がやってまいりました。

今年一年、皆さまにとってどんな年だったでしょうか。

世界各地で起こる悲しい出来事が耳に入る中でも、私たちの日常は続いています。紛争や災害、経済的困難、環境問題など、私たちの生活に直接的な影響がなくとも、他の人々の苦しみに心を痛めることがあります。

そのような時、私たち一人一人ができることは限られているかもしれませんが、小さな力でも集まれば大きな変化を生むことを忘れないでおきたいものです。

こうして年末に振り返ると、どんな小さな出来事も大切な一部分であることに気づかされます。

また、日常の中で優しさや思いやりを大切にすることで、周りの人々の支えとなり、少しでも希望の光を灯すことができるかもしれません。

*今日の着物*Today’s Kimono

「四季折々の着物と共に歩んだ一年」

今年も四季折々の行事やお茶会を通じて、カナダで着物を存分に楽しむことができました。

これも、隣組さまや日系センターさまでのバザーで着物や小物を購入したり「和の学校@東漸寺」にお越しいただいた皆様との交流の中で着付けを学び、楽しむことができたおかげです。

また、着物好きが集まる場所をご提供くださった東漸寺さまに心から感謝しております。

2024年の終わりに、私の着物生活を振り返ると、フィルム撮影や着付けの仕事を通じて多くのことを学び、着物を通じてさまざまなコミュニティや人々と触れ合うことができたことを実感しています。

伝統を尊重しながら進化し続ける着物は、これからも世界中で愛される文化遺産であり続けるでしょう。未来に向けて、着物がどのように進化し、広がっていくのか、私たちもその成長を見守り続けたいと思います。

*今年の最後のご挨拶*The last Greeting for the end of the year

来年は蛇年ですね。

蛇は脱皮を繰り返す生き物としても知られています。

脱皮は古いものを捨て、新しいものを迎え入れる象徴とも言われていますので、来年はさらに柔軟に、そして力強く新しい挑戦に取り組んでいける年になることを願っています。

どうか新しい年が、皆様にとってさらなる飛躍の年となり、健康で幸多き一年となりますよう心よりお祈り申し上げます。

コナともこ

「着物語り」

コナともこさんが着物の魅力をバンクーバーから発信する連載コラム。毎月四季折々の着物やカナダで楽しむ着こなしなどを紹介します。

2020年8月から連載開始。第1回からのコラムはこちらから。

コナともこ

アラフィフの自称着物愛好家。日本文化の伝道師に憧れ日々お稽古に励んでおります。

13年前からコキットラム市の東漸寺で「和の学校」を主宰。日本文化を親子で学び継承する活動をしております。

年間を通じて季節の行事に加え、お寺での初参り、七五三祝い、十歳祝い、元服祝い、二十歳祝い、結婚式、生前葬、お葬式などの設えと装いのお手伝いもさせていただいております。

*詳しくはコナともこ までお問い合わせ下さい。tands410@gmail.com

東漸寺は非営利団体で、和の学校の収益は東漸寺の活動やお寺の維持の為に使われています。

カナダ人の夫+社会人と大学生の3人娘がおり、バンクーバー近郊在住。

和の学校ホームページ https://wanogakkou.jimdofree.com/

インスタグラム https://www.instagram.com/wa_no_gakkou_tozenji/

フェイスブック https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100069272582016

東漸寺Tozenji Temple https://tozenjibc.ca/

コナともこ

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/tomoko.kona.98

Instagram https://www.instagram.com/konatomoko/?hl

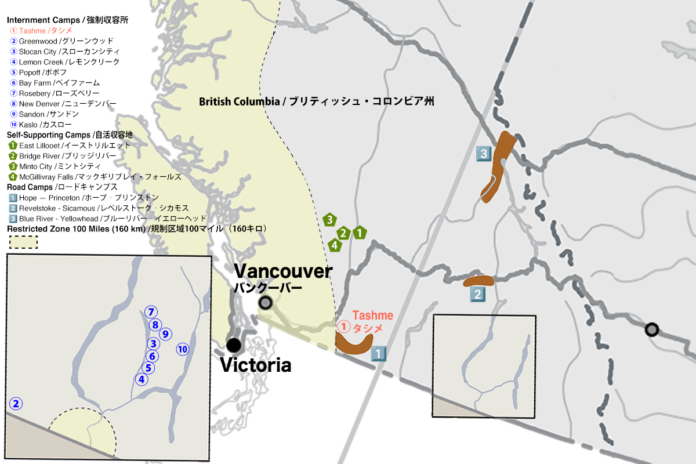

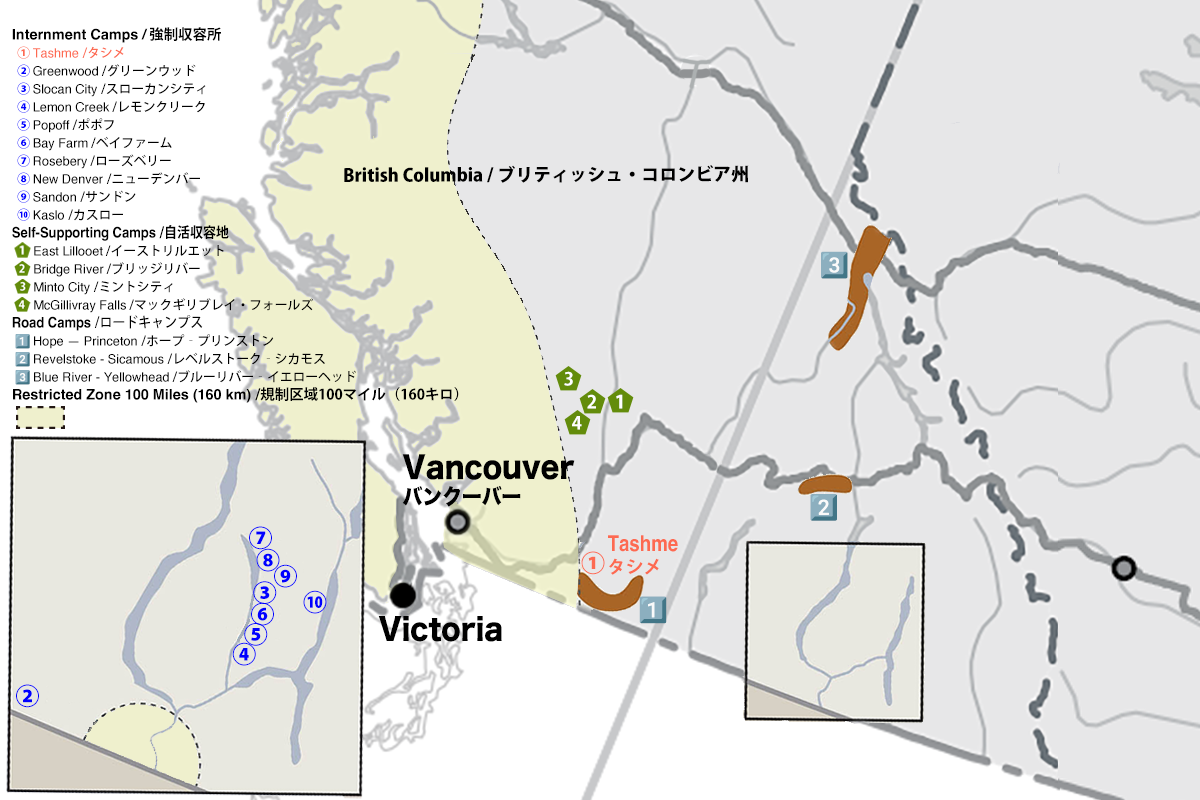

ロードキャンプ(高速道路建設キャンプ地):日系カナダ人物語

連邦政府は内閣条例によりブリティッシュ・コロンビア(BC)州、アルバータ州、オンタリオ州に道路建設キャンプ(ロードキャンプ)設置を1942年2月に決定した。

設置されたキャンプは、BC州に3カ所、ホープ‐プリンストン、レベルストーク-シカモス、ブルーリバー‐イエローヘッド、オンタリオ州に1カ所、ジャックフィッシュ‐シュレイバー。BC州の3カ所が安全保障上最優先とされた。

これらの3カ所のロードキャンプにBC州沿岸部から強制移動させられた日系カナダ人男性が送られた。

ホープ‐プリンストン・ロードキャンプ

ホープ‐プリンストン・ロードキャンプ は、ホープとプリンストンを結ぶ133キロメートルの道路建設のために設置されたキャンプ。

BC州に設置された3カ所のロードキャンプの中では最も「制限区域」に近く、日系人男性の家族は近くのタシメ収容所で生活していた。

レベルストーク–シカモス・ロードキャンプ

レベルストーク- シカモス・ロードキャンプは、レベルストークからシカモスまでのハイウェイ建設のために設けられたキャンプ。

日系人男性約500人が送られた。2年4カ月間でレベルストークから西へ44.5マイル(約71.6キロ)にわたるトランスカナダハイウェイの整備、改良、再建に従事した。

ブルーリバー‐イエローヘッド・ロードキャンプ

ブルーリバー‐イエローヘッド・ロードキャンプはアルバータ州に近く、1942年2月から始まりBC州とアルバータ州を繋ぐハイウェイの建設を目的としていた。

1942年のピーク時には約1,500人の日系人労働者が働いていたが、1946年5月には35人しかいなかった。

***

***

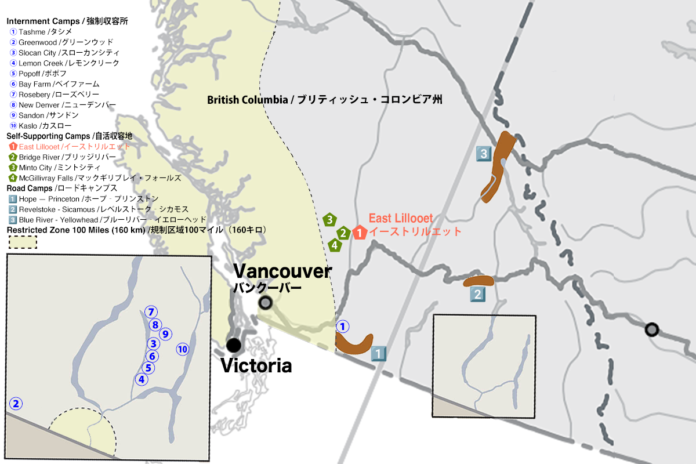

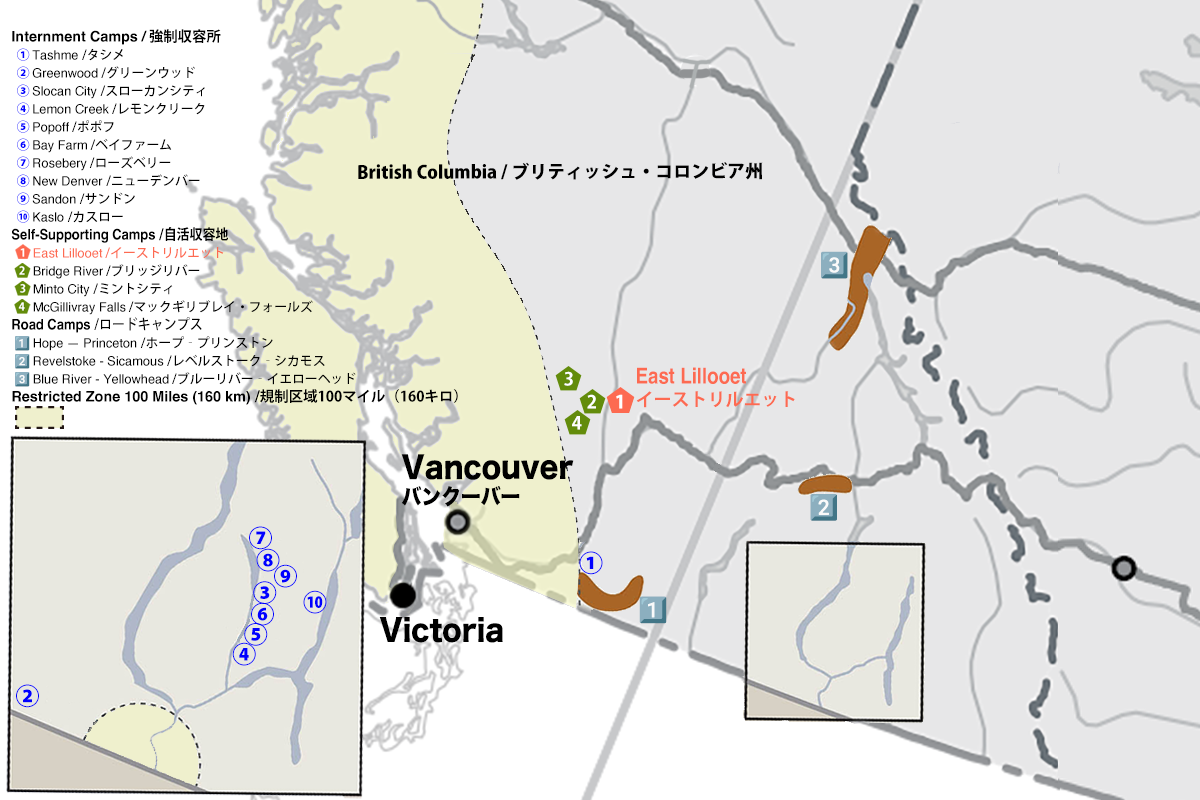

イーストリルエット(ブリッジリバー/ミント/マックギリブレイ・フォールズ):日系カナダ人物語

ブリティッシュ・コロンビア(BC)州山間部に位置するイーストリルエット、ブリッジリバー、ミント、マックギリブレイ・フォールズは、強制移動させられた日系カナダ人の収容地としては政府からの補助がない「自活収容地」として指定された地域である。

これらの収容地では、収容地外への移動は厳しく制限された。また、山間部での生活環境のため、資源不足や厳しい寒さと戦いながら自給自足の生活を送らなければならなかった。

イーストリルエット

イーストリルエットは1942年に設立された。リルエット周辺にあった数カ所の自活収容地で最大、バンクーバーから北東に約250キロにあった。この地域の収容所はフレーザー川の上流に位置し、300人以上が生活した。

生活環境は非常に過酷で、家も自分たちの手で建て、電気もなく、冬には厳しい寒さの中で生活を強いられた。また、水は初めはフレーザー川から運んでタンクに貯めてからろ過して使用するという不便な状況で、日系カナダ人たちはわずかな資源を活用し、農作業などを中心とした生活を送った。

ブリッジリバー

ブリッジリバー収容所は、かつての金鉱採掘と水力発電プロジェクトの廃墟に設置された自活収容地。日系人は、長く使われていなかった労働者が使用していたバラックでの生活を強いられた。農業を中心とした自給自足の生活を送った。

ミント

ミントは、かつて鉱業で栄えた地域だが戦時中には多くの鉱山が廃坑となり、ほとんど廃墟と化していた孤立地である。他の収容地と比べても特に人里離れた環境だったため、生活するには困難な場所だった。

マックギリブレイ・フォールズ

マックギリブレイ・フォールズは、100マイル(160キロ)「制限区域」のすぐ外に位置し、日系カナダ人は規制区域内のダーシー近くにあった製材所で雇用されていた。

***

***

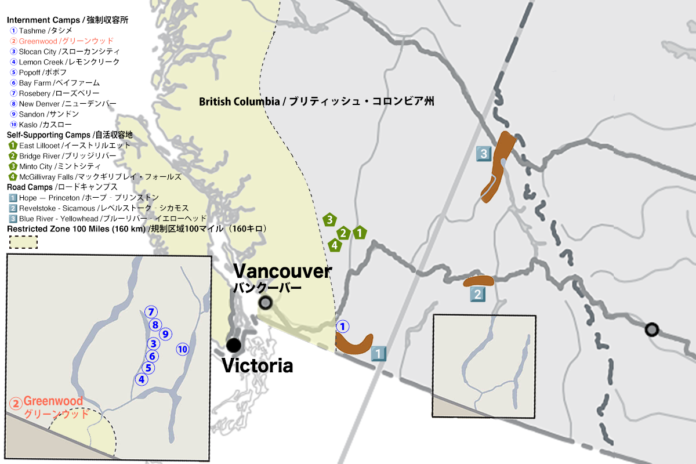

グリーンウッド、グランドフォークス:日系カナダ人物語

グリーンウッドは、カナダで初めて強制収容される日系カナダ人の受け入れに積極的な姿勢を示した町として知られる。グランドフォークスは「自活収容地」として家族が共同で生活を築いた町である。

グリーンウッドでの日系カナダ人の歴史

グリーンウッドは、カナダ政府が補助した日系強制収容所の一つだが、1942年に強制移動が始まった時に、他の多くの地域が受け入れを拒否する中で、この町は日系人を積極的に受け入れた。

当時グリーンウッドの人口は約200人まで減少し、町は衰退の危機に瀕していたため、W.E.マッカーサー・シニア市長が「日系カナダ人の受け入れを拒否しない」と新聞広告で明言。これにより、日系カナダ人が新たな居住地としてグリーンウッドに移動するきっかけとなった。

カトリック教会のベネディクト・クイグリー神父やフランシスコ会の修道女が、日系カナダ人を迎える上で重要な役割を果たした。

戦後とグリーンウッドの現在

1945年、カナダ政府は日系カナダ人に、ロッキー山脈以東か、日本に「帰国」するかという二者択一を迫った。しかし、グリーンウッドでは市役所と商務省が日系人を地域に留めるために政府に抗議文を提出。その結果、何百人もの日系カナダ人がこの町に残り、新たな生活を築いた。グリーンウッドは、戦後も日系カナダ人の生活基盤を提供し続けた数少ない地域の一つとなった。

2018年、グリーンウッドでは日系レガシーパークに「私たちは共に生きた」と題された約80枚の家族記念碑が設置された。この記念碑は、日系カナダ人と地元の白人家族が協力して地域を支え合った歴史を後世に伝えるもので、現在も数十人の日系カナダ人がこの町に住み続け、歴史と文化を守り続けている。

グランドフォークスでの日系カナダ人の歴史

グランドフォークスはグリーンウッドの東約40キロメートルに位置している。1939年からこの地に住むエズマツ・ナカタニ牧師らの働きにより、日系カナダ人が自主的に生活基盤を築いた「自活移動地」の一つである。ここには300人以上が移動した。

グリーンウッドやミッドウェイなど近隣の町と連携して、多くの日系カナダ人の生活基盤を整える支援が行われた。

***

***